The Negative Impact of the Department of Energy (DOE) 15% Overhead Rule on SBIR/STTR firms

The implementation of the 15% rule applied to the Department of Energy’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs will inadvertenty cripple the innovation for which this program has been justly recognized. In May 2025, the Department of Energy’s Office of Acquisition Management issued three Policy Flashes (PF) which limit the indirect rates allowed for grants and cooperative agreements. Collectively, these documents affect (1) nonprofits – in particular Institutions of Higher Education (PF 2025-26), (2) for profits – including both large and small business (PF 2025-27) and (3) state and local government (PF 2025-25). The stated purpose of the Policy Flashes is to improve efficiency and curtail costs where appropriate. PF 2025-27 clarifies that “The Department seeks to better balance the financial needs of financial assistance award recipients with the Department’s obligation to responsibly manage federal funds.”

However, what is left out of this balance is the profound and negative impact that this ceiling will have on small, advanced technology firms participating in DOE’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs. It will stifle their ability to advance DOE SBIR/STTR funded technologies into cutting edge, commercial products

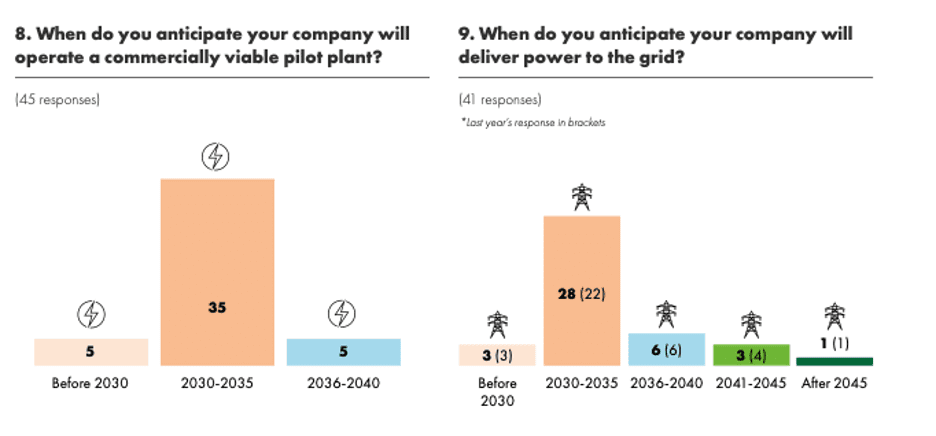

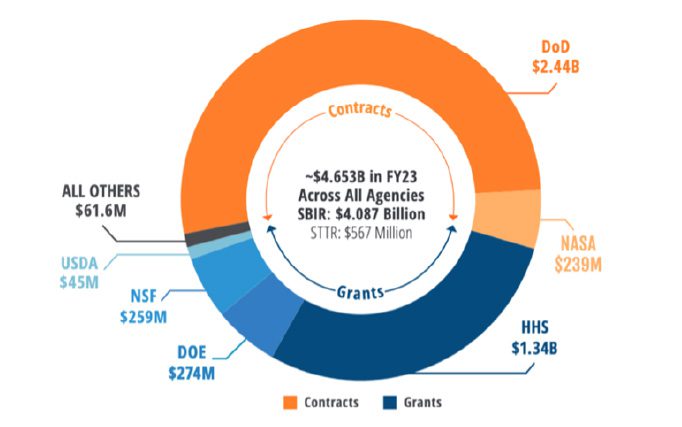

Funding for the SBIR/STTR programs comes out of extramural research and development funds. The federal government spent approximately $192 billion in FY23 on research and development. According to the National Science Board two-thirds of the FY23 federal R&D budget ($128 billion) went to extramural performers, while the remainder ($64.1B) went to intramural performers. Extramural performers include the three categories affected by the DOE Policy Flashes. In FY23, only $4.65B of the $128B spent on extramural R&D went to small business participating in the SBIR/STTR programs[1]. DOE which provides its SBIR/STTR awards as grants, accounted for just 5.89% of the total SBIR/STTR budget in FY23.

Figure 1: FY2023 SBIR/STTR Budgets by Agency

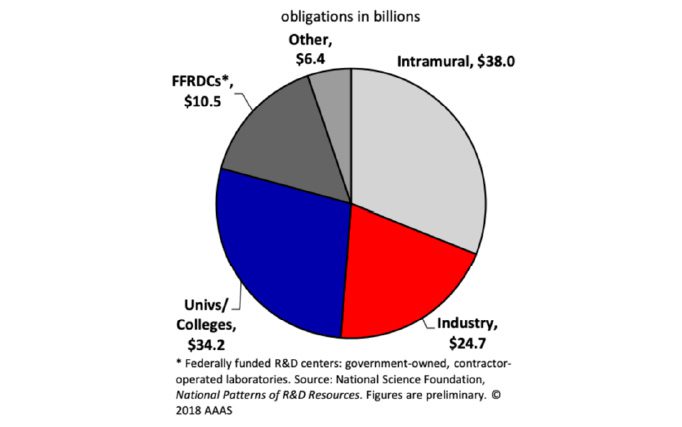

The amount of R&D funding that went to large business in FY23 is not readily available. However, one can gain insight into this information from a 2019 AAAS report. The following figure represents the distribution of federal R&D funding in FY16. The total amount of federal R&D funding spent on both intramural and extramural performers in FY16 was $113.8B. Of that total, $38B was spent on Intramural R&D, leaving $75.8B or 66% for extramural R&D. The combined SBIR/STTR budget in FY16 was $2.38B[2]. This represents 10.8% of the total extramural funding spent on industry ($24.7B) in FY16.

Figure 2: Federal R&D by Performer, FY2016

Most extramural R&D funding is awarded to LARGE business, not to small SBIR/STTR funded firms. I can’t speak to the ability of large business to absorb a 15% indirect cost ceiling. However, the mission of small, advanced R&D firms focused on basic and applied research limits their ability to supplement a 15% indirect cost ceiling. A potential side effect of PF 2025-27 is that DOE will lose some of its more seasoned performers to other Agencies participating in the SBIR/STTR program that use contracts as opposed to grants.

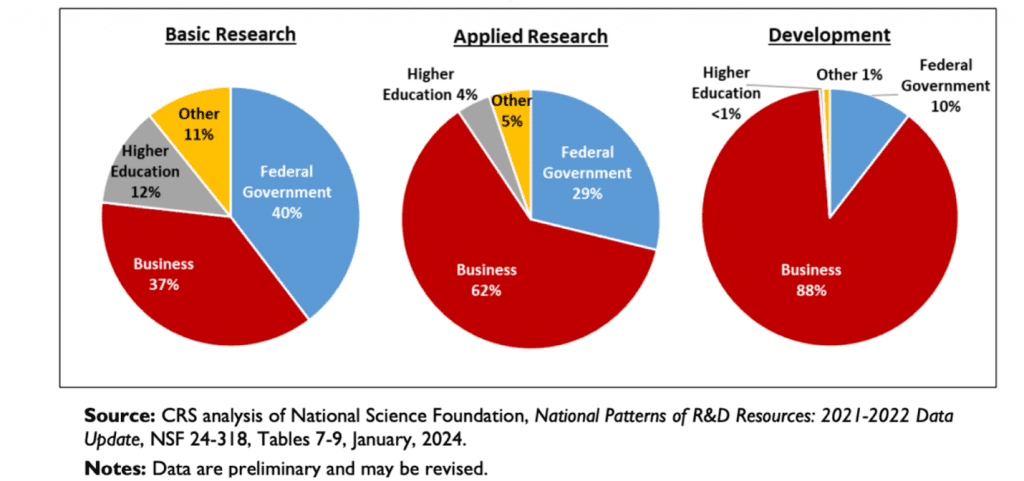

Although large business invests in R&D, studies conducted by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics indicate that the preferred model for large business is to have high-risk, basic and applied research funded by the federal government and then become involved when the technology is de-risked at the development stage (TRL 6-9). When the technology is sufficiently mature, the smaller entities could be acquired by a larger firm, intellectual property licensed-in, or joint ventures formed.

Figure 3: Composition of U.S. Basic Research, Applied Research and Development by Funding Sector, 2022.

PF 2025-27 states that “The Department plans to establish a maximum allowable dollar amount (stated in terms of a percentage of the total project award amount) that it will reimburse for allowable, allocable, and reasonable indirect costs under Awards. The percentage that will be reimbursable is inclusive of total indirect costs and fringe benefit costs.”

The 15% which is recommended in PF 2025-27 has historically been the de minimis and applies when the recipient does not have a current federal negotiated indirect cost rate. In practice, this tends to be used by start-ups which are often first-time applicants with minimal infrastructure. Start-ups with 1-3 employees use the de minimis rate as it does not require any back-up data. Fifteen percent of a Phase I DOE SBIR award of $200,000 is $30,000. Although this may sound like a lot to someone who has not run a business – health care benefits alone would take half of that in one gulp. If the company is a start-up working out of their home with minimal infrastructure, they might be able to make that work for their first year.

However, to grow a business so that it has the resources to both develop and commercialize a technology requires that a company add business functions and physical infrastructure. Gere Glover, the Executive Director of the Small Business Technology Council notes that the average indirect rate for maturing Department of Energy SBIR/STTR companies is approximately 50%. The 7% profit typically allowed to an SBIR/STTR firm by the Department of Energy cannot make up for the shortfall that the imposition of this 15% indirect rate will create. Implementation of this policy will damage their future and the ability of these companies to remain good suppliers of innovative technology to the Department of Energy.

PF 2025-27 states that “In circumstances where the Secretary has determined it is necessary and appropriate, the dollar threshold for payment of indirect costs may be modified for Award(s) to for-profit organizations that are subject to this policy.”

Grouping large and small businesses together that receive extramural R&D funds from the Department of Energy and then applying one indirect rate to all, ignores significant differences between large and small business. Large well-managed companies are financially stable and have an established and diverse infrastructure built over decades. They have personnel dedicated to product development, marketing and sales, distribution, manufacturing, quality, legal and the like. Large businesses make profit from the products that they sell and have cash reserves.

For small, advanced technology firms to become and remain viable entities on the path to financial independence requires time and resources. Examples of the typical expenses an SBIR firm must cover are available in examples that DOE provides small business on how to develop indirect cost models.[1] In this document a sample ledger provided by DOE depicts a 32% fringe rate and a 12.2% Indirect rate for a total of 44.2%, when combined. Funding is the life blood of a company and a 15% indirect rate is inadequate for a small, advanced technology firm.

Given the importance of the innovation that stems from the SBIR/STTR program to the Trump Administration, it is respectfully suggested that indirect rates for companies participating in the SBIR and STTR program be considered for separate benchmarks established after an analysis of historical data on SBIR/STTR indirect rates.

[1] The FY2011 reauthorization of the SBIR program increased the set aside to 3.2% of the extramural R&D budget and 0.45% for the STTR program.

[2] Small Business Administration, “ SBIR/STTR 2016 Annual Report to Congress,” 2019

[3] DOE National Technology Laboratory, “Negotiated Indirect Cost Rate Agreement and Indirect Rate Proposal Guidance,” https://netl.doe.gov/sites/default/files/2024-09/Negotiated-Indirect-Cost-Rate-Agreement-and-Rate-Proposal-Guidance.pdf